But today I want to focus on Dan Harmon's method, which is pretty much the lens through which I'll be looking at the other forms because, let's be honest, it's the best. Or at least it's the best one for me. I've studied story structure in the past--most notably Dan Wells' 7-point structure, as well as Lou Anders' "hollywood formula at Worldcon last year--but nothing cemented in my brainbox quite like Dan Harmon's. I'll briefly cover it here, but he's a lot better at explaining it than I am, so if you're interested I suggest checking out the following:

Story Structure 101: Super Basic Shit

Story Structure 102: Pure, Boring Theory

Story Structure 103: Let's Simplify Before Moving On

Story Structure 104: The Juicy Details (this one is by far the most comprehensive, and what motivated me to go out and actually read things like Joseph Campbell's The Hero with a Thousand Faces, but I suggest at least starting with 101 and 102 to get the basics down first)

Story Structure 105: How TV is Different

Story Structure 106: Five Minute Pilots

|

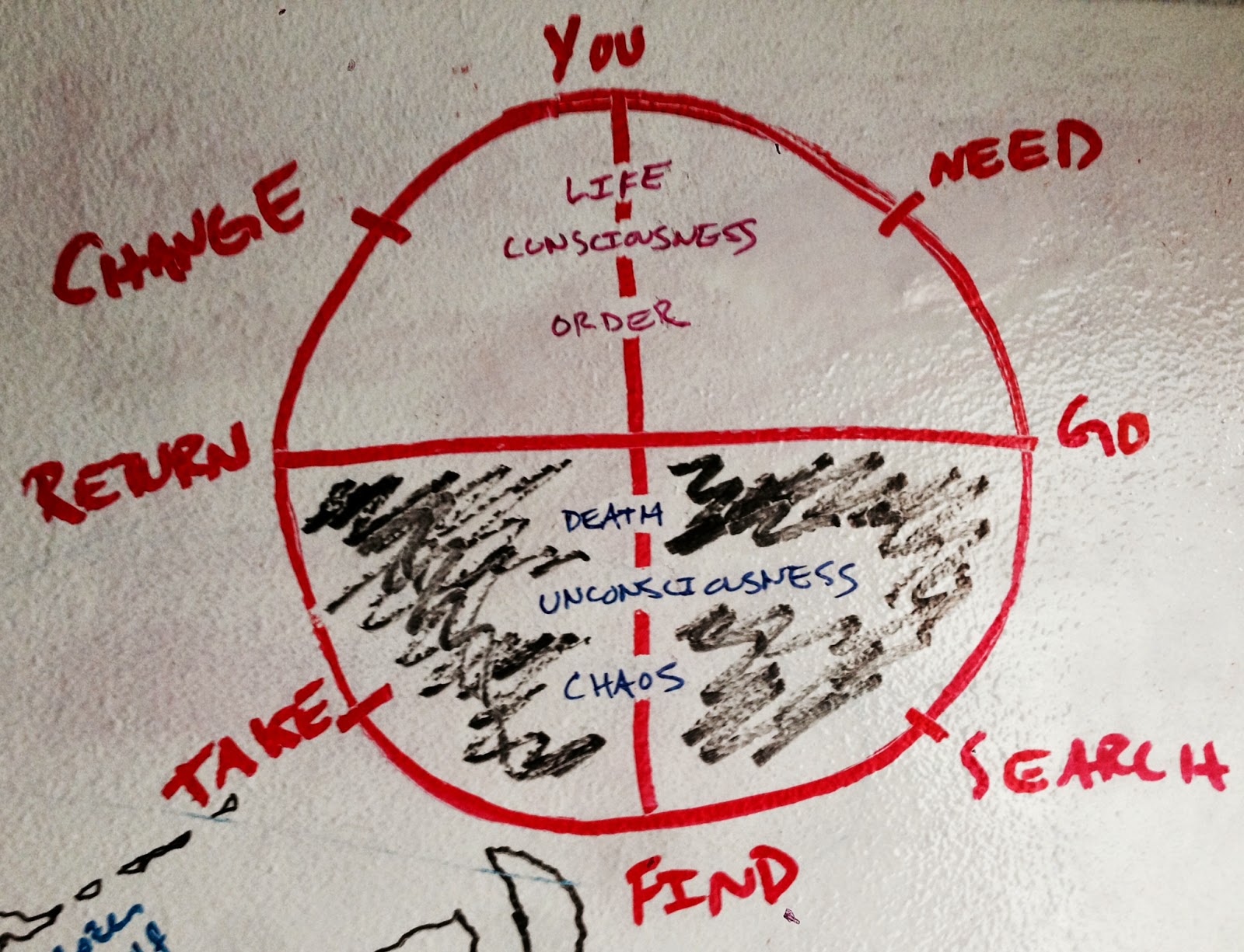

| This is from my white-board wall, btw. Have I mentioned I have a white-board wall? It's awesome. |

- You

- Need

- Go

- Search

- Find

- Take

- Return

- Change

Ignore the stuff written in the middle of the circle; I may or may not go into more detail on that later (but Harmon does, so again, if you're interested, check out those websites above). For now I'm just going to focus on the eight plot points.

The story begins with you, a character who either is you (metaphorically or otherwise) or with which you can empathize, sympathize, or to which you can relate in just about any way. Said character then discovers they need (/want) something. S/he then goes to a location, condition, or set of circumstances that is unfamiliar to them (hence the shaded lower half of the circle--it represents the unknown, the un/subconscious, the dark basement where chaos reigns) and searches for the thing s/he needs, often by/through adapting to the new circumstances. S/he finds what was needed, and takes control of his/her destiny and pays the price for it. Then the character returns to the comfortable/familiar situation, having changed in significant, life-altering ways, after such a fashion that s/he now has mastery over the world in which s/he lives.

It's simple, it's elegant, and what perhaps hits home most of all for me is how much Harmon emphasizes the every-day-ness of it all--this basic journey is reflected in all narratives. The circular pattern of descent into chaos and return to order drives all stories; Harmon says to

Get used to the idea that stories follow that pattern, [...] diving and emerging. Demystify it. See it everywhere. Realize that it's hardwired into your nervous system, and trust that in a vacuum, raised by wolves, your stories would follow this pattern. ("Story Structure 101")That, more than anything else, draws me to this method of structuring stories. Other methods, to me, seem a bit too focused on plot points and what-happens-where and get a little too specific for me. This, instead, simply teaches me what a story is, and then gives me the freedom to make what I want with it.

So, in the next couple weeks (months?), I'll be examining at least two (perhaps more) significant methods of story structure, but I'll use Harmon's formula as the lens through which to view them. I think it'll be interesting. If you do, too, come on back and check it out.

Sidenote: By the way, right now I'm watching Community (written by Dan Harmon). For the first time. So many friends have insisted I watch the show, and I've finally gotten a hold of the first few seasons. And okay folks, this show is DELIGHTFUL. It is brilliant and hilarious and uses all sorts of TV and film tropes in wonderfully curious ways. It's a little early to say for sure (I'm only a few episodes into season 2), but it may have already usurped my co-favorite sitcoms, Arrested Development and Seinfeld. It's that good. So, yeah, I might talk more about that one day, too.